KABUL — Taliban have launched a public awareness campaign to promote their morality law, a controversial edict that critics say is deepening restrictions on civil liberties, particularly for women.

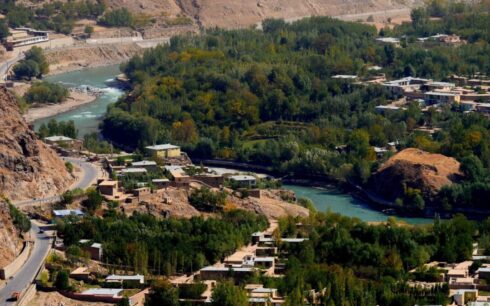

The campaign, organized by the Taliban-run Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, began this week in Bamiyan Province, where Taliban officials said the aim was to educate the public on the contents of the law, which was formally issued in September 2024.

According to a statement from the ministry, Taliban enforcers, known as muhasibs, have started conducting outreach in mosques and religious centers during the Islamic month of Muharram, emphasizing what they describe as the importance of “observing Islamic principles.”

“In the month of Muharram, muhasibs of the Ministry of Virtue and Vice in Wars District, Bamiyan, launched programs to enhance public understanding of the law and promote religious discipline,” the ministry’s statement read.

The law, signed by Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, consists of four chapters and 35 articles, and has been published in the Taliban’s official gazette. Among its most contentious provisions are Article 13, which classifies a woman’s voice as awrah (something that must be concealed), and Article 17, which prohibits the display of human images, including in media broadcasts.

Human rights activists argue that the law has intensified repression, particularly for women, and has created growing divisions within the Taliban’s own leadership.

“This law has severely restricted civil liberties and particularly undermined the rights of women,” said Abdul Ahad Farzam, a legal researcher and human rights activist. “It has also increased the risk of arbitrary detention and abuse under the guise of moral enforcement.”

Despite the prohibition on imagery, several senior Taliban officials, including their chief minister Mohammad Hassan Akhund, his deputies, Abdul Ghani Baradar and Abdul Salam Hanafi, Taliban defense minister Yaqoob Mujahid, and Taliban interior minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, continue to appear in photographs and videos distributed through state-run and Taliban-aligned media outlets.

Only a handful of high-ranking officials, including Mohammad Khalid Hanafi, Taliban minister for virtue and vice, Neda Mohammad Nadim, Taliban’s higher education minister and a close aide to their leader, Abdul Hakim Sharaee, Taliban’s justice minister, and Abdul Hakim Haqqani, Taliban’s chief justice, have refrained from public imagery in apparent compliance with the law.

Since the law’s passage, local television stations in some provinces have increasingly restricted visual content. Media monitoring groups report that image broadcasting has been banned in at least 15 provinces, many of them under the influence of hardline Kandahari factions loyal to Akhundzada.

Women in several provinces say the law has severely affected their daily lives, particularly Article 13, which bans women from traveling without a male guardian and restricts their access to public transport.

“This law has made life unbearable,” said one woman in Bamiyan, who asked not to be named for security reasons. “We are not only silenced but also isolated. Every day brings new restrictions.”

Taliban have defended the law as consistent with Islamic values. However, human rights organizations say it represents a broader institutionalization of repression and deepens Afghanistan’s isolation from international norms on gender equality and press freedom.